Your cart is currently empty!

🧱 Lego & Leonardo: A Brief History of the Commonplace Book

Have you ever thought about how great ideas are constructed?

I used to think it was a sudden flash of inspiration (and a skill I just didn’t have.)

Over the years, I’ve learned that creativity is system: there’s an input (information) that we process in order to produce an output.

If you want to improve your output, the place to start is the input (the information you collect).

In other words: garbage in, garbage out.

Tiago Forte (author of Building a Second Brain) says it this way:

But once you find information worth keeping, where do you put it?

One of the places that people collect those mental building blocks is the commonplace book.

A commonplace book is a place to connect bits of information from other various sources.

But the commonplace book isn’t a new concept. In fact, great thinkers have been using commonplace books to work with their ideas for hundreds of years!

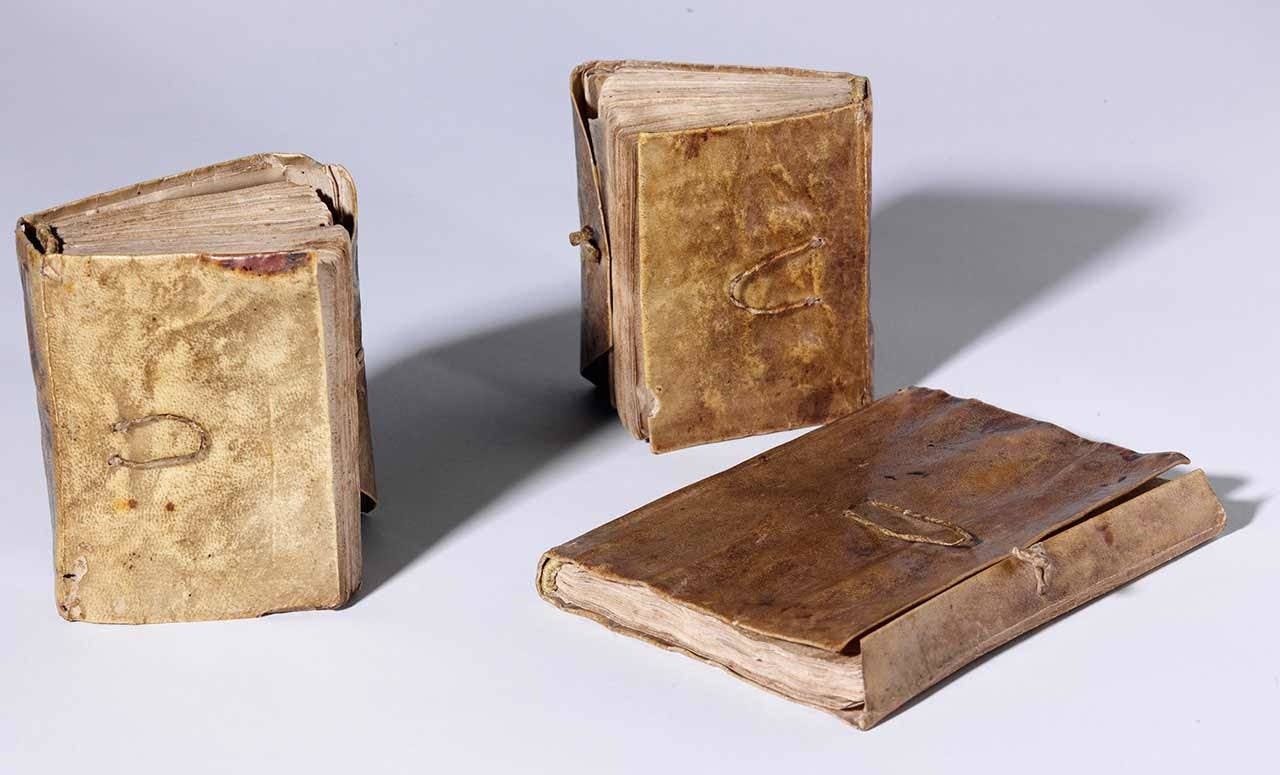

One of the early examples of a commonplace book is Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, where he wrote about his exploration of art and science.

|

|

He kept 5 of these notebooks (bound into 3 volumes) which are collectively known as The Codex Forster. They date from roughly 1487 to 1505, and you can actually view the entire collection online here.

It’s fascinating to browse through these notebooks and see all the building blocks of ideas that Leonardo collected. Notes, sketches, anything that was inspiring was captured in these notebooks and served as the foundation for many of the world’s most incredible inventions.

Fast forward a few centuries, and we have digital tools for thought that allow us to connect things in powerful ways that Renaissance-era inventors like Leonardo could only dream of.

Our commonplace books may be digital instead of analog, but the approach is still the same: capture what resonates, then make something new out of it.

And it’s easier to do that when we embrace the idea of atomic notes.

Atomic notes are small notes that contain a single complete idea. This concept that hit me after reading Atomic Habits by James Clear. In the beginning of the book, James shares a couple of definitions for the word atomic:

- an extremely small amount of a thing; the single irreducible unit of a larger system

- the source of immense energy or power

I realized that this applies to ideas too, and I believe connecting your ideas works best when you break your notes down into the smallest logical pieces.

The real creative power of the digital commonplace book is unlocked when you break things down into their component parts (atomic notes).

Think of these atomic notes as individual mental Lego bricks. Each atomic note is a single brick that you can use to make something new. Yes, they likely came in a set with other bricks (for example, ideas from books that you read), but that doesn’t mean those bricks can’t be taken and used for something completely different.

Just like with Lego bricks, the smaller the building blocks, the more things we can make from them. (It’s way more fun to play with Lego bricks than their giant Duplo cousins.)

If you want to learn more about using atomic notes in Obsidian, I recorded a YouTube video about this:

Wether or not you use Obsidian though, I encourage you to have a place to develop your ideas. It could be analog or digital, just make sure you have a place to collect things and to be selective about the things you collect. As Austin Kleon (author of Steal Like an Artist) writes:

Your commonplace book doesn’t have to be fancy – just a place to keep your mental Lego bricks so you can take them apart and book them back together.

You don’t have to be a Renaissance-era inventor to benefit from having a place to play with your ideas.

— Mike Schmitz

P.S. I talked to Tiago Forte awhile back for the Focused podcast. It was a great conversation and we dove into this topic a little deeper. Click here if you want to check out that episode.

P.P.S. I really enjoyed Tiago’s book, and highly recommend it. Click here if you want to download my notes, or click here to check out the Bookworm episode about it.